Scholars have long emphasized the role that public trust has in strengthening democracy (Barnard 2001; Buchanan 2002; Citrin 1974; Dahl 1971; Lipset 1959). In his recent book entitled Can Governments Earn Our Trust? D. F. Kettl provides a description of trust as both a dependent and independent variable formed by circumstances that the American public has gone through. He explains it as “a force that shapes expectations and that is a product of past experiences” (2017, 41).

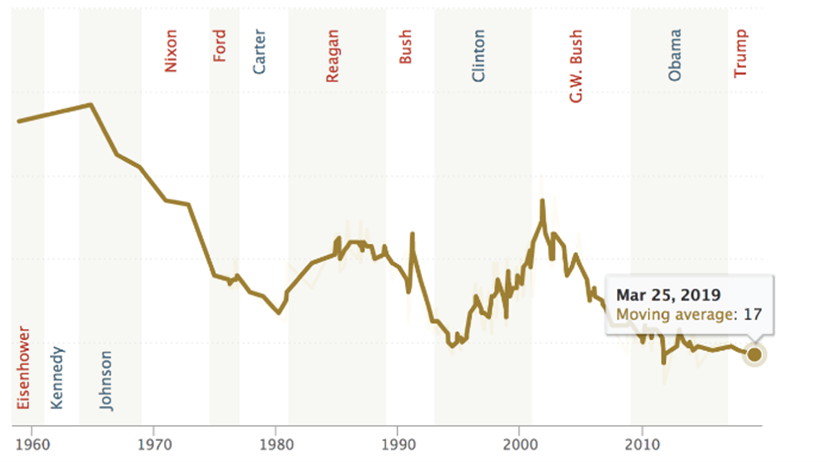

Since the 1960s, public trust in government and political institutions has eroded in nearly all advanced democracies around the world (Dalton 2005). Although the problem is pervasive, it is perhaps more evident in the United States, where the percentage of Americans who distrust the government in Washington is growing. The portion of Americans that trust the government always or most of the time has been declining since the John F. Kennedy presidency in the early 1960s (see Figure 1).

The reasons for this decline are not always clear. Much of the foundational research about trust in government points to the role of the economy, social and cultural elements, and polarization (Miller 1974; Mishler and Rose 2001). More recently, scholars have highlighted the role that race has in shaping trust (Heideman 2020; Maltby 2018; Nunnally 2012; Price 2012; Scherer and Curry 2010; Schwei et al. 2014; Wilkes 2015; Yeager et al. 2017). In this paper, I explore the roots of Americans’ distrust in government by focusing on the factor of race.

The Roots of Distrust

According to Garry Orren (1997), starting in the mid-1960s, there was a continuous decline in trust that intensified over the next thirty years. Orren notes that skepticism among the public could transform into cynicism. However, as Jack Citrin points out, it is important to distinguish between mistrust and a healthy level of skepticism within democratic cultures. The origins of distrust and dissatisfaction vary, but the research suggests a steep fall that started with Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration. Trust reached an all-time low in 2011 and has remained at similar levels ever since (Pew Research Center 2022). The original distrust in government by Americans can be generally traced back to overreach by politicians (Nye 1997).

According to the Pew Research Center, “Public trust in the government remains near historic lows. Only 17% of Americans today say they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (3%) or “most of the time” (14%)”.

Fig. 1. Percentage of Americans Who Trust the Government Always or Most of the Time. From: Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019”. U.S. Politics & Policy.

An abundance of evidence suggests that many government programs are satisfactory in the function they were originally designed to perform (Kettle 2017; Pew Research Center 2022). Despite this, Americans seem to exhibit exceedingly high expectations and end up eventually feeling somewhat thwarted. As Citrin (1997) points out, distrust in government is becoming more evident in political events, attitudes, and expectations.

What do Americans expect from their government? The issue of what the public demands from their representatives is a thorny one. According to some scholars, Americans do not really want to become too involved in the political process because a significant number of them prefer a “stealth democracy,” instead of a more active and participatory version of government (Hibbing and Theiss 2003). Many people are indifferent to government policies and do not care about holding the government accountable except in exceptional circumstances. This seems to ring especially true when considering the way most people approach politics. As long as their lives can go on and they are marginally better off year after year, there is no reason to get political. The public wants to know that there will be an opportunity to participate, but few have the intention of exercising those rights. They feel strongly, but only about a few matters, and actually prefer not to get involved.

For example, Americans do worry about political conflict leading to social disruption, such as the violent uprising against the government on January 6th, 2021, which they perceive as an indication of an anomaly in an ideal democratic system. Given the choice, they would rather concern themselves with issues other than politics, but that has not stopped them from failing to trust their government. The expectations Americans have of their government are excessively high, making disappointment inevitable. The declining trust exhibited by many Americans, regardless of their political views, party affiliations, age, gender, and race is evident. Economic reasons, social and cultural elements, and the polarization of American parties are all solid explanations to explore; however, this paper focuses on the roots of distrust for the government from a racial perspective.

Race and the Roots of Distrust

According to the Pew Research Center, the country’s confidence in government has been declining at an accelerated pace across racial and ethnic lines. For example, white non-Hispanics, black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics indicate an all-time low level of distrust in government. During the Republican administrations of Reagan and G.W. Bush more whites than blacks expressed more confidence in their government to do the right thing. In contrast, during the Democratic presidencies of Clinton and Obama, blacks were more likely than whites to show trust in government.

It is important to acknowledge the different ways that various racial and ethnic communities process their expectations of government. More importantly, it is crucial to understand how implausible expectations might lead to distrust. Americans can experience trust of political incumbents, the electoral system, public policy, and the economy in very different ways (Wilkes 2015). These diverse perspectives are processed heterogeneously according to race. They caused different outcomes on the trust of black and white Americans because political confidence is processed in different ways by these groups (Wilkes 2015). Today, the United States is facing great political division, and one of the main reasons for that phenomenon is how different races perceive the government’s performance.

White Americans and Distrust

On the one hand, in order to fully understand the issue of race in politics, it is important to comprehend how the current ethnic majority in the United States, the white population, feels about the government. Whites began to lose trust in their representatives in the 1960s, as public policy grew more conservative. Data shows the correlation between conservatism and trust. Racial prejudice, measured in terms of anti-black stereotypes influence white Americans’ beliefs about the trustworthiness of the government and racial policy towards African Americans. Thus, even when racial policy issues are no longer on the agenda, negative attitudes about the policy may persist and inform judgment about government trust (Filindra, Kaplan and Buyuker 2002). It is also worth considering that many whites became less trusting of the government as a result of civil rights, due to the result of the influence that the Civil Rights Movement exerted to grant more power to other groups.

For white Americans, efficient governing represents a well working administration that accomplishes short term goals. It is important to consider why trust among whites would decline as policy becomes more conservative. Perhaps it is getting more conservative because whites (by and large) are electing political conservatives to office. For many, distrust in the U.S. government results from dissatisfaction with the performance of their elected officials, which leads them to perceive the administration as a slow responding and inefficient political machine. This can become an incentive to change the government or even ignore its existence. For white Americans, if they are dissatisfied with elected authorities, they look for change through electoral replacement, or show their dissatisfaction by not voting for any of the two major parties. Some scholars suggest that any significant increase in the percentage of independents hints to an increase in government distrust (Keele 2005).

In order for the majority of the white population to remain faithful to their government, it would require the political party of their affiliation, once in power, to perform productively. In this regard, experts agree that trust is represented by short-term success. However, the association of political trust with being satisfied about the performance of the incumbent administration is only true for white Americans (Wilkes 2015). Lack of efficiency and dissatisfaction with the results of their chosen party is what pushes many, especially white Americans, to join the right-wing American Independent Party or the Libertarian Party.

Black Americans and Distrust

On the other hand, black Americans’ political distrust comes primarily from the history of exclusion experienced since their forced arrival in the continent. At many points in history, blacks have been less trusting of the government relative to whites (Abramson 1983). As it has been widely documented, the black community has been excluded from most political activity until the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Remarkably, it was not until the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, that they were granted the right to vote and came closer to playing a significant role in the American political arena. It is therefore understandable for black Americans to feel a lack of trust in their government, given the little opportunity that has been afforded to them.

Unhappiness stems from racial inequality and discrimination, which has led to a general feeling of malaise within the political system. Their disadvantages are embedded within a racist system, making it difficult for them to feel like valued citizens. This sentiment causes them to refuse the acceptance of the Protestant work ethic and instead inculpate the political system, which has caused their significant decline in trust.

Mistrust among blacks, however, seems to lead to a vague support for the government more than for their representatives and the policies they attempt to advance (Avery 2007). The discontent for the political system in some African Americans is eminently tied with the racial inequalities experienced in their past. For many, the recent heightened lack of trust in the government dates back to the 2000 election between George Bush and Al Gore. The Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore was a crucial point in the loss of confidence in government among blacks. This is apparent in the way the evidence points to blacks’ perception of the Court’s decision as illegitimate, incrementing their mistrust in the government (Avery 2007). After this legal episode, blacks’ distrust in government has broadened even more widely.

It is also important to note that, while all other racial groups in America are seeing a net increase in their incomes, black Americans have received only a shrinking slice of the economic pie. They are getting worse off, year after year. It is hard to trust a government that defends an economic system that punishes them.

Hispanic Americans and Distrust

Ironically, Hispanic Americans, the most recent immigrants to the U.S., tend to be the most trusting of their government. The notion of being aliens in a foreign country allows for many Latinos to strongly believe in the American government in a very optimistic way. Their desire of assimilation, plus their impetus to trust their new country prompts them to believe in the political system of their adopted home.

The truth is, for many Latinos, compared to their country of origin, the U.S. government does not appear as corrupt as theirs, granting the American political process a chance to prove itself wrong for a while. They strongly believe in the concept of the American dream and its association with the political ideals of freedom, democracy, and transparency because they recognize they are being implemented more thoroughly than in their home countries (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010).

However, similarly as it occurs with black Americans, as Latinos spend more time in the country, their encounter with racial discrimination pushes them further from their auspicious views. This leads them to reflect on their positions and to reconsider whether or not they should trust the government. In general, non-fully assimilated immigrants tend to optimistically trust their new government more than those more integrated into the American fabric (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010). This proves that American-born and raised children of immigrants grow up with a certain degree of suspicion about their government compared to their blindly faithful parents who may have not been raised in America.

Distrust in America

In general, most Americans share an overall similar perception of what an untrustworthy government looks like and what is needed for an efficient administration. Human beings tend to trust what they know and that explains why most Americans increase their fondness for their government when their affiliated party is in power but lose that trust once it is no longer holding the reins of power.

It makes sense that people trust their own political party as well as those who they share similar beliefs with. Ultimately, they hope that their party will have their best interest in mind. That always seems to be preferable to the opposing faction, which they are less familiar with, but innately perceive as the “other”. For most Americans, the trust in their politician incumbents has become so vigorous that when their party wins a congressional or presidential election, which translates into trust for their government because they interpret it as signal that their group holds some control and power within the system (Keele 2005).

Division across party lines has become very significant for each side. However, the majority of the American people, regardless of their demographics, are satisfied with the government if their elected officials have integrity. More importantly, they are satisfied if they are performing well because general belief tends to associate mistrust as a result of despondency with incumbents and their policies, not as a cynical stand against government. This is true for all groups (Avery 2007).

Even though party tribalism prevents some constituents from recognizing the benefits that initiatives promoted by the other side can offer them, one federal program that has received wide approval regardless of party or racial considerations has been Medicare. It is important to note that both Medicare and Medicaid were heavily debated when they were first proposed and originally there was a lot of opposition to them. The public healthcare protection system known as Medicare has demonstrated that it is flexible, efficient, improves the health of its participants, and provides significantly more access to care compared to private insurance (Katch 2017). Additionally, Medicare costs approximately 22 percent less than private insurance (Katch 2017).

In spite of this strong evidence, because of political division, some Americans might still need to be convinced that certain programs are good for them even if the initiative comes from the other political side. On the one hand, this doubt can be explained because white Americans argue that trust is defined by short term success from their elected officials. On the other hand, black and Hispanic Americans feel that the main issue is a distrust of the system itself. Since trust seems to divide along racial lines, this program may satisfy short-term interests as well as broader racial equity issues.

Finally, to end with a positive note, it is important to take into consideration that most Americans agree that government itself is not the problem, but rather the incumbents and the partisan policies they produce. As Jack Citrin states, it is crucial to differentiate between dissatisfaction with current government policy positions, dissatisfaction with the outcomes of ongoing events and policies, mistrust of incumbent officeholders, and rejection of the entire political system (Citrin 1974).

Therefore, to find a largely satisfactory answer for most, it probably will require a new approach. Giving programs names like “Trump Care” or “Biden Care” might not be the best way to achieve wide support or success. In any case, since mistrust has been partially provoked by popular dissatisfaction with the governing process, contemporary democracies have been implementing numerous reforms to expand access, increase transparency, and improve the accountability of government. Political reforms are necessary to implement change, but using language that is non-partisan could go a long way to facilitate the advent of a new era of cooperation. A less divisive approach could facilitate much-needed reforms and the implementation of programs that work for all.

References

Abrajano, Marisa A. and R. Michael Alvarez. 2010. “Assessing the Causes and Effects of Political Trust Among U.S. Latinos.” American Politics Research 38 (1): 110- 141.

Abramson, Paul R. 1983. Political Attitudes in America: Formation and Change. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

Avery, James M. 2007. “Race, Partisanship, and Political Trust Following Bush versus Gore (2000).” Political Behavior. 29 (3): 327–342.

Barnard, Frederick M. 2001. Democratic Legitimacy. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Buchanan, Allen. 2002. “Political Legitimacy and Democracy.” Ethics 112 (4): 689– 719.

Citrin, Jack. 1974. “Comment: The Political Relevance of Trust in Government.” American Political Science Review 68 (3): 973-988.

Dahl, Robert. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dalton, Russell J. 2005. “The Social Transformation of Trust in Government.” International Review of Sociology 15 (1): 133-154.

Filindra, Alexandra, Noah J. Kaplan, and Beyza E. Buyuker. 2022. “Beyond Performance: Racial Prejudice and Whites’ Mistrust of Government.” Political Behavior 44 (2): 961–979.

Heideman, Amanda J. 2020. “Race, Place, And Descriptive Representation: What Shapes Trust Toward Local Government?” Representations 56 (2): 195-213.

Hibbing, John R. and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse. 2003. Stealth Democracy: American’s Beliefs About How Government Should Work. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Katch, Hannah. 2017. “Medicaid Works: Millions Benefit from Medicaid’s Effective, Efficient Coverage.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Washington, D.C.: 1-8.

Keele, Luke. 2005. “The Authorities Really Do Matter: Party Control and Trust in Government.” The Journal of Politics 67 (3): 873-886.

Kettl, Donald. F. 2017. Can Governments Earn our Trust? Malden, MA:Polity Press.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1959. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105.

Maltby, Elizabeth. 2017. “The Political Origins of Racial Inequality.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (3): 535-548.

Miller, Arthur H. 1974. “Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970.” American Political Science Review 68 (3): 951-972.

Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust?: Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62.

Nunnally, Shayla C. 2012. Trust in Black America: Race, Discrimination, and Politics. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Nye, Joseph S. Jr. 1997. “Introduction: The Decline of Confidence in Government.” In Why People Don’t Trust Government, eds. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Philip D. Zelikow, and David C. King, 1-18. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Orren, Garry. 1997. “Fall From Grace: The Public’s Loss of Faith in Government.” In Why People Don’t Trust Government, eds. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Philip D. Zelikow, and David C. King, 77-108. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pew Research Center. 2019. “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019.” U.S. Politics & Policy. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/04/11/public- trust-in-government-1958-2019/

Pew Research Center. 2019. “Trust in Government by Race and Ethnicity.” https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/chart/trust-in-government-by- race-and-ethnicity/

Price, Gregory N. 2012. “Race, Trust in Government, and Self-Employment.” The American Economist 57 (2): 171–187.

Scherer, Nancy and Brett Curry. 2010. “Does Descriptive Race Representation Enhance Institutional Legitimacy? The Case of The U.S. Courts.” The Journal of Politics. 72 (1): 90–104.

Schwei, Rebecca J., Kelley Kadunc, Anthony L. Nguyen, and Elizabeth A. Jacobs. 2014. “Impact of Sociodemographic Factors and Previous Interactions with The Health Care System on Institutional Trust in Three Racial/Ethnic Groups.” Patient Education and Counseling 96 (3): 333–338.

Wilkes, Rima. 2015. “We Trust in Government, Just Not in Yours: Race, Partisanship, and Political Trust, 1958–2012.” Social Science Research 49: 356-371.

Yeager, David S., Valerie Purdie-Vaughns, Sophia Yang Hooper, and Geoffrey L. Cohen. 2017. “Loss of Institutional Trust Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Adolescents: A Consequence of Procedural Injustice and a Cause of Life-Span Outcomes.” Child Development 88 (2): 658–676.

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.