Defenders of the winner-take-all method of the Electoral College predict that implementing a national popular vote would cause less-densely populated cities and states to be forgotten in presidential elections. This paper takes a quantitative approach to evaluate that claim.

On five occasions the president has been elected without attaining the popular vote. Is this a feature, a bug, or a necessary evil of the Constitution? In order to address this question, I will explore the debates made both for and against the Electoral College during the Philadelphia Convention of 1787. Despite the intentions of the framers of the Constitution, it seems clear that the Electoral College does not operate as intended. Considering this, I will present two sides of the contemporary debate over whether the United States should eliminate the Electoral College and adopt a national popular vote. Defenders of the Electoral College fear that only large urban areas and the most populous states would receive attention from presidential candidates if a national popular vote was used. However, I find empirical evidence that suggests otherwise. Examining the outcomes of several senatorial elections demonstrates that there is evidence to suggest that relying on a national popular vote system would not cause vast swaths of Americans to be ignored more than they currently are under the winner-take-all method of the Electoral College.

During the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 the delegates considered several methods of electing the president. Early in the Convention, Edmund Randolph proposed that the president be elected by a national legislature. However, this method of election perturbed many delegates at the Convention, causing them to consider several alternative methods for selecting the president (Madison 1985). One possible alternative to Randolph’s electoral scheme was a national popular vote (Madison, 1985). Ultimately, the delegates rejected this proposal too because they were concerned that the general population lacked the knowledge and discretion to be responsible voters. Moreover, there was a general concern that if statehood was not somehow incorporated into the presidential election, then the larger, more populous states would dictate every general election.

The Electoral College was proposed as a compromise because it did not wholly rely on either establishing a national legislature or a direct national popular vote. Instead, the number of electoral votes each state received in the Electoral College was to be the sum of the number of Representatives and Senators each state had in Congress. This allows for the will of the populace to be accounted for (via the allotment from the House of Representatives) and the will of the states to be accounted for (via the allotment from the Senate). Thus, the Electoral College was designed to ensure that there was a check on the will of the people and that each state had a separate say in the presidential election.

The Electoral College, despite the Framers’ intentions, developed into a different system than anticipated. The Electoral College was intended to be a body of free-thinking individuals that were trusted by their communities to exercise their discretion during presidential elections. However, the electors have historically acted as a body of lifelong party affiliates who merely confirm the popular vote of their respective state. The gradual rise of political parties since the framing has contributed to this situation by sorting voters into binary camps. Moreover, partisanship was abetted by the structure of elections in the United States. The “unit rule” system or “winner-take-all” method of election makes the margin of victory in a state irrelevant. If a candidate wins by at least one vote, then they are guaranteed 100% of that state’s electoral votes. As a result, many attempts to alter or reform the Electoral College have been made throughout the years.

One of the major arguments made against the Electoral College is that it forces candidates to spend the majority of their campaign resources in battleground states. Elections in battleground states are highly competitive, so they end up having great importance in the outcome of presidential elections. Due to the increasing polarization of contemporary political parties states have been swinging further left and right, making the margin of victory a likely shoo-in for one candidate before the race even begins. The idea of “battleground states” and “flyover states” has further gained in significance since the early 2000s when only seven of the 50 states were decided by a margin less than 3% (Torry 2012). Due to the fact that in the 2016 election 96% of the campaign events took place in just 12 states (National Popular Vote), there seems to be truth in former Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s comment that “the nation as a whole is not going to elect the next president. Twelve states are” (Walker, 2015).

Conversely, advocates of the current system maintain that if the “winner-take-all” method was to be changed such that a national popular vote method were adopted, the weight of the election would be disproportionately placed onto large cities and states. Candidates would focus their campaigns in cities and states that yield the highest amount of participation for their time and money and ignore the rest of the country. Republican strategist Hogan Gidley stated that “[a nationwide popular vote] would reduce voters’ access to the candidates since events in big cities would be more likely to be massive rallies than more accessible town-hall meetings held in places like Iowa and New Hampshire.” (Beckwith 2016).

If the winner-take-all method was replaced by a national popular vote, then there would certainly be significant changes to presidential campaign strategies. However, I wonder if this kind of institutional change would cause, as proponents for the Electoral College contend, candidates to neglect rural areas during their campaigns. In order to address this question, I analyzed the way in which candidates for the U.S. Senate have campaigned. Three criteria must be met to apply the trends from a statewide level to a nationwide level. It is necessary to analyze a competitive race in a year that did not have a presidential election in a state with specific rural and urban areas. Presidential elections are typically competitive, and they tend to have a significant impact on senatorial elections in terms of fundraising, party attention, and general campaigning. Moreover, states with distinctive rural and urban areas need to be selected so that they would be somewhat representative of the urban and rural areas in America.

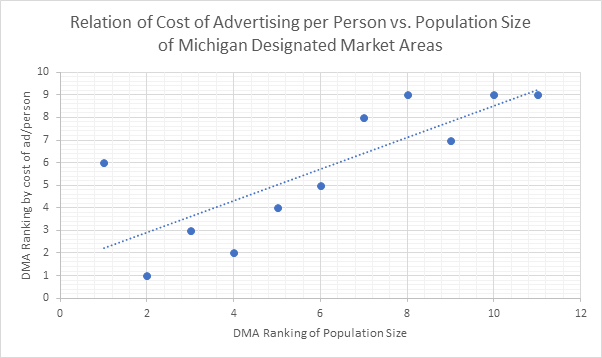

Graph 1: Relation of Cost of Advertising per Person vs. Population Size of Michigan Designated Market Areas in the 2014 Senate Election

Graph 1 shows the statistical findings of the 2014 Michigan Senate race. The data show that in an electoral system analogous to a national popular vote most designated market areas (DMAs) in the state received media attention rather than solely the most-populated areas (data on file with author; available on request). The only DMAs that didn’t see any attention were areas that were not fully located in Michigan (e.g. Green Bay-Appleton DMA which includes just one county in Michigan) which makes sense because candidates would want to spend their money in places that are likely to get a return for their money.. Admittedly, the DMAs with the largest population did receive the most attention which held true with the notable exception of the Detroit DMA. Detroit was ranked first in population, but in the bottom half for cost of advertising per person, at just $2.67/person. This figure represents an amount 36% less than the statewide average of $3.83/person. This shows that the candidates do not necessarily spend the most money per person in the most populated areas where they could potentially reach and influence the greatest number of voters. Other factors, such as past voter turnout rates and demographics, likely play a larger role in determining where candidates choose to spend their money. Thus, there is reason to doubt that candidates would solely campaign in large cities in an election decided by the popular vote.

Table 1 and Table 2: Events and Mentions on Kyrsten Sinema and Martha McSally’s Facebook Pages (March 2018-November 2018)”

Table 1: Kyrsten Sinema’s Facebook Page:

| County | Number of Mentions/Events | Percent of Total Mentions/Events | Percentage of Population |

| Maricopa and Yavapai (Peoria) | 5 | 6.67% | 2.46% |

| Maricopa | 20 | 26.67% | 60.61% |

| Pima | 37 | 49.33% | 14.73% |

| Yuma | 1 | 1.33% | 3.18% |

| Santa Cruz | 2 | 2.67% | 0.74% |

| Pinal | 2 | 2.67% | 6.14% |

| Coconino | 0 | 0.00% | 2.07% |

| Yavapai | 4 | 5.33% | 3.24% |

| Coconino and Yavapai (Sedona) | 1 | 1.33% | 0.10% |

| Cochise | 2 | 2.67% | 1.84% |

| Mohave | 0 | 0.00% | 3.01% |

| Apache | 0 | 0.00% | 1.04% |

| Gila | 0 | 0.00% | 0.79% |

| Navajo | 1 | 1.33% | 1.60% |

| Greenlee | 0 | 0.00% | 0.16% |

Table 2: Martha McSally’s Facebook Page:

| County | Number of Mentions/Events | Percent of Total Mentions/Events | Percentage of Population |

| Coconino | 3 | 3.16% | 2.07% |

| Maricopa | 54 | 56.84% | 60.61% |

| Pima | 17 | 17.89% | 14.73% |

| Pinal | 2 | 2.11% | 6.14% |

| Santa Cruz | 0 | 0.00% | 0.74% |

| Yuma | 5 | 5.26% | 3.18% |

| Navajo | 1 | 1.05% | 1.60% |

| Cochise | 3 | 3.16% | 1.84% |

| Gila | 0 | 0.00% | 0.79% |

| Yavapai | 7 | 7.37% | 3.24% |

| Mohave | 3 | 3.16% | 3.01% |

| Apache | 0 | 0.00% | 1.04% |

| Graham | 0 | 0.00% | 0.55% |

| Greenlee | 0 | 0.00% | 0.16% |

Furthermore, in the 2018 Arizona Senate election between Democrat Kyrsten Sinema and Republican Martha McSally, one can see in Table 1 and Table 2 that the candidates made a conscious effort on their Facebook platforms to mention a variety of counties and cities (and post pictures of them visiting these areas) regardless of the number of people living there. While they did concentrate their efforts on the most populous areas, they seemed to do so proportionately, especially for McSally’s campaign. For Sinema’s campaign, Pima and Maricopa saw the highest percentage of events, likely because 76% of the state’s population lives there. Even though it is likely that the candidates could have won the state by just focusing on these counties, they didn’t only visit these counties; they also focused their attention elsewhere, perhaps demonstrating the fact that other factors such as voter demographics are important to candidates when they are looking to turn out the vote. For reference, the counties (excluding Pima and Maricopa) that received 29.33% of events only accounted for 24% of the state’s population. These results suggest that in a national popular vote campaign most areas of the country would receive some sort of media or event related attention since every vote would count in every jurisdiction in an equal manner. A clear caveat to this is that there is no reason to believe that states that currently do not receive much attention (e.g. Wyoming) would receive more attention if the system depended on the national popular vote.

In the end, these results indicate that most areas would receive media attention during a presidential campaign when the national popular vote is decisive. Admittedly, there is certainly a need for more data analysis to provide more evidence for my findings. I am currently processing senatorial elections in Virginia and Iowa in a similar analysis as Michigan, and I intend to analyze all of the states involved in the 2014 Senate election that fit the criteria of extrapolation. While there is no way to be certain that there would be an even distribution of campaign activity if the United States’ electoral system was based on a national popular vote, further analysis will likely provide data and a manner with which to better explain candidate behavior.

References:

Beckwith, Ryan Teague. 2016. “Electoral College: How Popular Vote Campaigns Would Work.” Time. November 17, 2016. http://time.com/4573821/electoral-college-popular-vote-campaigns/.

Lovelace, Ryan. 2015. “Walker: ‘The Nation as a Whole Is Not Going to Elect the next President, 12 States Are.'” Washington Examiner. September 01, 2015. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/walker-the-nation-as-a-whole-is-not-going-to-elect-the-next-president-12-states-are.

Madison, James. 1985. Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Torry, Jack. 2012. “Modern elections decided by a few states: That’s why Obama visits OSU today to start campaign.” Columbus Dispatch. May 5, 2012.

National Popular Vote. n.d. “Two-thirds of Presidential Campaign Is in Just 6 States.” Accessed December 12, 2018. https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/campaign-events-2016.

Iowa Community Indicators Program. n.d. “Urban Percentage of the Population for States, Historical.” Accessed December 8, 2018. https://www.icip.iastate.edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states.

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.