In contrast to the United States policy of protecting hateful expression, a survey of democracy indices indicates that dozens of democracies have hate speech laws that restrict it. This challenges assumptions of debate in the United States by showing such restrictions are feasible in a free society.

In the United States free speech is considered one of our most cherished values, with everyone from the lawyers of the American Civil Liberties Union to the scholars of the American Enterprise Institute rallying to its defense (Rubin 2018). In keeping with the expansive doctrine informally known as “free speech absolutism,” restrictions on speech are strictly scrutinized and various forms of “content discrimination” are routinely struck down for fear of a slippery slope (Downing 1999; Heinze 2006; Martinez 2015; Gladstone 2019). In Matal v. Tam (2017), a case addressing a racially offensive trademark, a Supreme Court majority argued that “a law that can be directed against speech found offensive to some portion of the public can be turned against minority and dissenting views to the detriment of all.” This is only one of the latest examples in a decades-long series of rulings that restrictions on hate speech (and content restrictions more generally) are impermissibly dangerous to democracy. The forms of expression that have been protected in such cases include cross-burning in R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992) and Virginia v. Black (2003); a Neo-Nazi march in NSPA v. Skokie (1977);an inflammatory public speaker in Terminiello v. Chicago (1949); a KKK rally in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969); and funeral picketing in Snyder v. Phelps (2011).

Justice Douglas, defending free speech absolutism in Terminiello, argued that“there is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.” This isn’t simply a legalistic argument about what the Constitution says, but a hypothetical imperative that if we are to avoid the undemocratic “standardization of ideas,” then we have no choice but to take an absolutist approach to free speech. More broadly, the animus against hate speech laws for the sake of democratic health implies mutual exclusivity between freedom and restriction.

But is the slippery slope argument actually true? Is restricting hate speech reallyso dangerous? Is protecting it reallyso necessary? I sought to answer these questions by using various measures of freedom to identify democracies around the world, and then researching said democracies for the presence of restrictions on hate speech laws. When we fear the consequences of restrictions on hate speech or insist that we must protect it to avoid a negative outcome, we are making a claim that can be scrutinized: if restricting hate speech inflicts catastrophic harm on freedom of speech, and if freedom of speech is so essential to democracy, then we should expect very few successful democracies in the world to have such restrictions. The argument that we simply must protect hate speech or else endanger our liberty is much weaker if democracies elsewhere actually restrict it while remaining free societies.

In examining whether this is the case, I define a hate speech law as one that is intended to restrict speech that expresses or promotes hostility or prejudice against people due to their personal characteristics without falling into categories of already impermissible speech in the U.S. For example, a law against inciting genocide is not a “hate speech law” but an “incitement to genocide” law that’s focused on protecting racial groups. While inciting genocide is hateful, and singling out incitement against specific groups is discriminatory, this is already illegal under a general statute (18 U.S. Code § 1091). Since it targets a specific kind of already impermissible speech instead of a general category of “hate speech,” it is not a valid counterexample to American free speech absolutism. Moreover, I differentiate between laws that directly targethate speech and laws that indirectly effect it. A workplace harassment law that prohibits the use of a racial slur toward a coworker is not a law against hate speech anymore than a burglary ordinance is a law against crowbars; slurs are just one way create a “hostile workplace environment,” just as a crowbar is one way to break into a house. By contrast, the United Kingdom’s Public Order Act of 1986 purposefully targets hate speech under several offenses in an entire section entitled “Racial Hatred.”

While I primarily focused on national-level criminal laws, civil and administrative laws were included under this definition as well, along with local laws, as countries with such laws differ substantially enough from U.S. practice to be worth studying as counterexamples. For example, administrative law in Trinidad and Tobago forbids telecommunications licensees from broadcasting any program that “degrades” groups or encourages discrimination, while in the U.S. a clause against trademarks that “disparage” others was struck down in Matal v. Tam. Similarly, local laws in foreign countries are notable since local hate speech laws have been struck down in the U.S.: R.A.V v. St. Paul struck down a cross-burning ordinance,while Japan allows municipal governments to restrict anti-Korean speech (Higashikawa 2018).

My original research utilized the Democracy Index, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Using 60 indicators in 5 categories (electoral process and pluralism, civil liberties, functioning of government, political participation, and political culture), it measures countries on a 0.00-10.00 scale and classifies them as Full Democracies, Flawed Democracies, Hybrid Regimes or Authoritarian Regimes. Of 167 countries, 76 are Flawed or Full Democracies. Using legal databases, research from human rights organizations, law journals, national records, and other resources, I then searched for hate speech laws in all 76 democratic countries. Among the 64 countries with hate speech laws was the highest-ranked democracy in the world (Norway), as well as all other countries in the top 24. At 25th place, the United States is actually the highest-ranked country that does not have any.

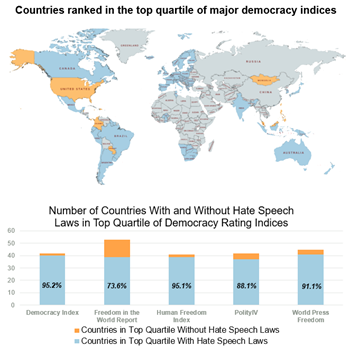

Of course, measuring “democracy” is somewhat subjective, and it’s possible the peculiarities of the Democracy Index produced this extraordinary result. Yet when we examine alternative measures of political freedom, the same pattern emerges. In the bar graphs below, I have taken a top-quartile survey of countries on the Democracy Index, Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Report, PolityIV, and Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index. As we can see, countries with hate speech laws made up 73-95% of the top quartile depending on the index. In other words, it is consistent across multiple measures that a majority of the world’s freest and most democratic countries actually restrict hate speech.

Furthermore, this correlation is consistent over time. The Democracy Index covers 12 years from 2006-2019, and the average score of democracies with hate speech laws has exceeded the average of those without in every single one of them. More specifically, the average of democracies with hate speech laws has remained an average of .88 points higher on the 0.00-10.00 scale than those without, with the difference in a given year never falling below .78 and reaching as high as .97.

However, perhaps the historical trend is better shown in a more specific way. By showcasing individual countries that have hate speech laws, we can get a closer view of what a democracy that restricts hate speech looks like. The United Kingdom’s Public Order Act of 1986 outlines an entire section for “Racial Hatred” offenses that apply to speech, written material, plays, broadcasts, and recordings. French hate speech regulation is centered around the 1972 “Pleven Law” (Bleich 2015). Using PolityIV since it’s the only scoring index that goes back this far, we can see that since 1986 the UK remained a solid 10 on its -10 to 10 scale for 29 years, until dropping and leveling out at 8 from 2016-2018. Since the 1972 Pleven Law, France actually improved its score from 8 to 9 in 1986, remaining there ever since.

More broadly speaking, there is also a decades-long international regime dedicated to regulating hate speech. In 1965 the United Nations codified an obligation to restrict it, ratifying the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Article 4(b) mandates that states shall make “punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred.” The treaty entered into force in 1969 and has over 182 state parties today. Similary, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights would enter force in 1976, with Article 20(2) declaring that “any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.”

From Norway to Papua New Guinea the free world restricts hate speech, showing that perhaps free speech absolutism isn’t as necessary as is commonly thought. Yet it is important to note the limitations of this study. Firstly, and most important, this study makes a narrow claim using shallow data. Based on this data, it is impossible to determine whether a given country’s rank on a given freedom index is actually in spite of its hate speech laws. All I can definitively say is that there are many democracies with hate speech laws, which is enough to draw the narrow conclusion that hate speech laws do not necessarily need to be avoided to protect democracy. This study doesn’t prove that hate speech laws aren’t unhealthy to a democracy, just that at the very least they aren’t fatal. In other words, I cannot show that hate speech laws are good policy, only that they are not so inevitably disastrous that they must automatically be disregarded.

I must also admit survivorship bias: by only looking at democracies for hate speech laws to see if they were lethal to democracy, I might as well have determined whether a chemical was lethal by only looking at living people who have been exposed. While I have to stress that the finding that it’s possible to be a strong democracy and restrict hate speech still stands on its own (i.e. Norway is still a healthy democracy with hate speech law no matter how many dictatorships have them), it’s important to also know whether or not authoritarian regimes have hate speech laws, and if they abuse them the way we fear they will be if enacted in the U.S. A future research project might first look at all countries with hate speech laws and then determine which ones are democratic.

Showing that it’s possible for democracies to restrict hate speech without falling into authoritarianism is admittedly a low a bar to pass. But if we want to debate the merits of any “alternatives,” then it helps to know if they are even possible in the first place. The dozens of democracies with them indicate that hate speech laws are in fact feasible in a free society. The policy of speech protection is uniquely American among democracies. We can still believe that hate speech laws are bad policies, and the evidence I’ve found cannot comment on whether they are good. But we can and should continue to debate whether or not our free speech absolutism is the best approach, and I hope my findings about other countries and their “alternatives” can inform further discussion.

References

Bleich, Erik. 2015. “French Hate Speech Laws Are Less Simplistic than You Think.” The Washington Post, January 18, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/01/18/french-hate-speech-laws-are-less-simplistic-than-you-think/

Brandenburg v. Ohio. 395 U.S. 444 (1969). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/395/444/

Downing, John D.H. 1999. “‘Hate Speech’ and ‘First Amendment Absolutism’ Discourses in the US.” Discourse & Society 10 (2): 175-189.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2020. “Democracy Index 2019: A Year of Democratic Setbacks and Popular Protest.” The Economist. https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index Gladstone, Brooke. 2019. “Against Free Speech Absolutism.” WNYC Studios, Sticks and Stones Podcast, October 11, 2019. https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/against-free-speech-absolutism

Heinze, Eric. 2006. “Viewpoint Absolutism and Hate Speech.” The Modern Law Review 69(4): 543-582.

Higashikawa, Koji. “Japan’s Hate Speech Laws: Translations of the Osaka City Ordinance and the National Act to Curb Hate Speech in Japan.” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal 19(1): 4-5.

Marshall, Monty G. and Ted Robert Gurr. 2019. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018.” Center for Systemic Peace. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html

Martinez, Andreas. 2015. “I Used to Be a Free Speech Absolutist. Charlie Hebdo Changed That.” The Washington Post, January 26, 2015. www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/01/26/i-used-to-be-a-free-speech-absolutist-charlie-hebdo-changed-that/

Matal v. Tam. 582 U.S. ___ (2017). supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/582/15-1293/#tab-opinion-3749203

National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie. 432 U.S. 43 (1977). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/432/43/

R.A.V. v. St. Paul. 505 U.S. 377 (1992). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/505/377/

Reporters Without Borders. 2019. “2019 World Press Freedom Index: A Cycle of Fear.” https://rsf.org/en/2019-world-press-freedom-index-cycle-fear

Repucci, Sarah. 2020. “Freedom in the World 2020: Democracy and Pluralism are Under

Assault.” Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2020/leaderless-struggle-democracy

Rubin, Michael. 2018. “Swastikas, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and the Slippery Slope of

Twitter’s Speech Policing.” American Enterprise Institute, August 20, 2018. https://www.aei.org/articles/swastikas-recep-tayyip-erdogan-and-the-slippery-slope-of-twitters-speech-policing/

Snyder v. Phelps. 562 U.S. 443 (2011). supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/562/443/

Telecommunications Authority of Trinidad and Tobago. 2001. The Telecommunications Act 2001. https://tatt.org.tt/Portals/0/Generic%20Concession%20Document.pdf

Terminiello v. Chicago. 337 U.S. 1 (1949). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/337/1/

United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. 1969. “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, entry into force January 4, 1969. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cerd.aspx

United Nations Human Rights Committee. 1976. “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, entry into force March 23, 1976. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx

Vasquez, Ian, and Tanja Porcnik. 2019. “The Human Freedom Index 2019.” A report by the Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute, and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/human-freedom-index-files/2019-human-freedom-index-update-2.pdf

Virginia v. Black. 538 U.S. 343 (2003). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/538/343/

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.

Compass is an online journal that provides a space for the work of talented undergraduates who have original and well-articulated insights on important ideas and issues relating to American democracy understood in the broad contexts of political philosophy, history, literature, economics, and culture.